A blockchain-based supply chain process could facilitate instant tracking, preserve privacy through a private chain with preauthorization, reduce costs related to updating information, enable automatic payments and, in general, improve automation (Chang et al., 2019). This is particularly interesting in the context of the energy sector, where renewable energy and carbon credits are intangible tradable items. The application of blockchain to supply chain management is particularly intriguing in relation to the monitoring of workers’ rights, slavery and unethical behaviors because it contributes to tracking and assuring the entire process. Rozario and Thomas (2019) suggest the creation of a second blockchain owned by an auditor and connected to the accounting blockchain of the first client in a network. In this way, auditors could extract data from firms’ blockchains and perform smart audit procedures within these blockchains.

Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a UK private company limited by guarantee (“DTTL”), its network of member firms, and their related entities. DTTL and each of its member firms are legally separate and independent entities. DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) does not provide services to clients. In the United States, Deloitte refers to one or more of the US member firms of DTTL, their related entities that operate using the “Deloitte” name in the United States and their respective affiliates. Certain services may not be available to attest clients under the rules and regulations of public accounting.

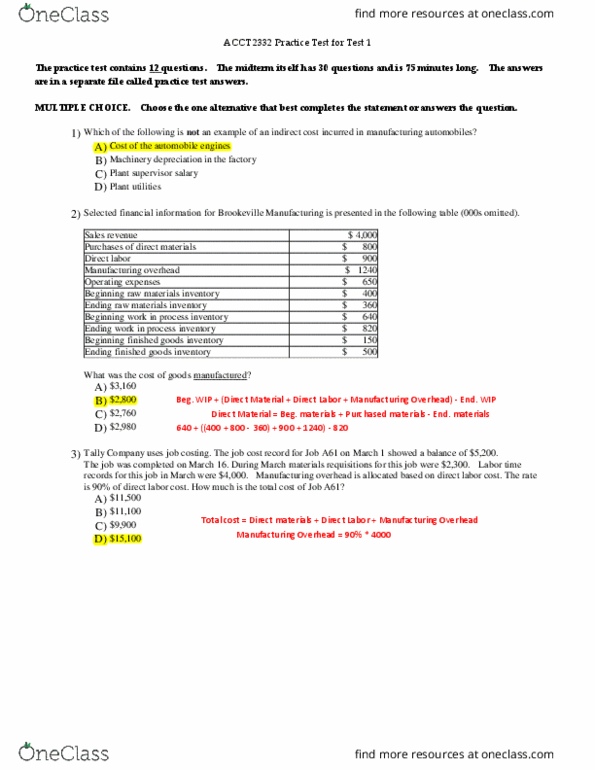

- Deloitte’s 2019 Global Blockchain Survey found that 53 percent of respondents say blockchain has become a critical priority for their organizations (up 10 points from the prior year), and 83 percent see compelling uses for blockchain.

- After a thorough analysis of the literature and existing scenarios, this study scrutinizes the contemporary blockchain applications employed in the accounting and auditing sector and discusses the prospects and challenges of introducing blockchain technology in the auditing industry with a legal and regulatory lens.

- Tiberius and Hirth (2019) confirm that auditors’ expectations align with those of academics, who believe that the role of auditors will not be filled by blockchain technology.

- Monitoring what happens in real time rather than testing (selectively) and reconciling what happened in retrospect is a substantial departure from contemporary audit techniques.

Fatz et al. (2019) use blockchain technology to create a system that issues certificates of arrival for goods, which are relevant in the VAT context for transactions between two businesses located in different EU countries. We believe it is urgent to fill this gap with systematic insights into the potential of and challenges facing blockchain technologies in accounting practice and research. This impact has raised questions about the nature of cryptos, their function as payment systems, their performance and the role of central banks. As blockchain is an innovation, the financial market also had to learn to value companies that announced that they were pursuing account reconciliation services investment in this new technology.

Without the benefit of skilled audit professionals to provide deep thinking and sound judgments and to make sense of findings―and without an innovative methodology that evolves while being grounded in common standards, regulations, and guidelines―technology by itself loses its context and purpose. When audit technologies are at their most powerful, they work together as part of an effective audit methodology that incorporates the judgment and experience of auditors, all of which come together to provide very high-quality audits and generate insights that inform larger business risks and opportunities. The promise of this powerful combination is not just a game changer for the audit world, but also a benefit for organizations and a boost to investor confidence overall. As blockchain technology continues to advance and new and different uses are found, it will be up to the accountancy profession to ensure that its promises of transparency and accountability are fulfilled. Imagine certified public accountant the power of this technology combined with Artificial Intelligence (AI) where the testing for discrepancies through analytical review could take place in real time and without the risk of missing transactions or the auditor having a blind spot in analyzing the information. Blockchains and their almost immediate provision of an immutable record of transactions provides for shared transaction information, automatically synchronized across each location.

Figure 4.

The rapid evolution of technology is quickly changing the way business is conducted across all industries, even some that are centuries old. For example, artificial intelligence (AI) can drive down the cost of health care by more accurately determining correct drug dosages for patients and potentially reducing errors. It can also assist doctors with preliminary diagnoses of conditions such as skin cancers and help hospitals reduce wait times. (2018), “Auditing with smart contracts”, The International Journal of Digital Accounting Research, Vol.

Blockchain Technology: Shaping the Future of the Accountancy Profession

Second, it investigates how accounting and auditing practices are impacted by blockchain. Third, it contributes to the accounting literature with its discussion of the potential future research trends related to blockchain for accounting. The agile design of Deloitte COINIA also means it can be used today not only for crypto assets but also for a broader base of digital assets, and beyond, as they are supported by the business community in the future. These can include supply chain tracking, digital rights management, real estate title transfer, and other forms of real-world asset digitalization. Deloitte COINIA is an extension of Deloitte’s award-winning Cortex platform, a cloud-based data platform that harnesses the power of data by securely and seamlessly integrating data acquisition with data preparation and analytics.

We opted not to exclude papers that were published in journals with moderate- to low-impact factors. Moreover, as blockchain is a recent topic, we decided to include conference papers and book chapters. For example, robotic process automation can standardize and speed workflows, while AI and analytics help auditors visualize and understand entire populations of data and point to correlations, anomalies, and outliers, thereby improving risk identification and focusing on what matters most. It is also very likely that, in the next few years, more audits will be augmented by cognitive technologies, which confer many of the same benefits and may portend even greater potential than other technologies for the audit.

Author Services

The first is proposed by Ijiri (1986), who suggests the use of a third layer to measure momentum income. The second idea, which refers to accounting blockchain, is that of Grigg (2005). Furthermore, a blockchain accounting system that is integrated with smart contracts “can self-execute or self-enforce the agreements signed by two parties” (Cai, 2021, p. 9).

Figure 2.

Gonzalez (2020) shows that peer-to-peer (P2P) lending decisions are influenced by the gender of borrowers and herding behavior. Figure how to determine customer credit terms 6 shows a cooccurrence heatmap of the main authors’ keywords (more than five occurrences) in this cluster. Table 3 provides some quantitative data (total citation and CPY) regarding the studies with the highest impact on this topic. Figure 5 shows a cooccurrence heatmap of the main authors’ keywords (more than five occurrences) in this cluster.

Bavassano et al. (2020) focus on the shipping industry, where blockchain can be used to improve international administrative procedures, but a lack of standards, particularly those imposed by regulation, represent the highest barriers in this context. Blockchain might be helpful in terms of accounting for renewable energy and carbon credits, which are intangible tradable items created to provide additional financial incentives to clean energy producers (Ashley and Johnson, 2018; Tang and Tang, 2019). Hojckova et al. (2020) study the success factors of blockchain-based P2P electricity trading. Although there was some doubt on the matter before an official interpretation was provided by the IFRS Interpretations Committee in June 2019, cryptoassets should currently be accounted for as intangible assets (IAS38) or inventory (IAS2). Regarding taxation, cryptocurrencies should be VAT exempt, and when they are directly taxed, transactions should be treated as production events for miners or as exchanges of foreign currencies in all other situations. Having companies with cryptocurrencies on their balance sheets also presents some auditing issues because there is not a third party and transactions are pseudoanonymous in some cases.

Leave a Comment